People don’t like changes. That’s why they rarely like redesigns. So the only change the Twitter community would appreciate was adding a button for editing tweets, but Twitter didn’t add the editing button.

The changes Twitter made were way more controversial and framed as an "Accessibility" thing.

- Twitter changed the system font with a new custom one.

- They switched to a high contrast color scheme.

- They changed the color of the buttons.

The redesign probably helped those with low vision or color-blindness. But it made Twitter inaccessible for people with astigmatism and dyslexia (the new font), and color-contrast and photosensitive migraineurs (the new color scheme). Even people without any visual impairments complain of headaches after scrolling through the updated interface.

All of those novelties are default. Users can’t change the font or reduce the contrast. They can only express their outrage — express with a fierce and unruly force.

Users hate Twitter's new font.

The new opinion-dividing font is called Chirp (Twitter, Chirp, you get it). In early August the company replaced the previous system font, and for some people, it has gone unnoticed. At the same time, tons of people found the new font barely readable.

Complaints are not a surprise. Font readability is in large part a matter of habit — after all, medieval Europeans believed the gothic typefaces were pretty convenient. That brings us back to the statement about changes that people hate. Naturally, a standard system typeface feels better than a font you’ve never seen before. Most social media know that and use operating systems’ default fonts. Twitter also knows that. In the update announcement, they say that changes “might feel weird at first.”

We can trust Twitter when they say we’ll get used to the new font. But we may doubt when Twitter says they introduce the font that is harder to read as an update for better accessibility. When the company first showed Chirp to the public half a year ago, they said the font was for “having a holistic brand,” and this reason makes much more sense.

We’ve recently written about how brands balance on the dizzying path between unique and usable. In short, most apps sacrifice their distinguishing features because they want to be more convenient for users. Design uniformity helps us to switch between dozens of apps effortlessly.

Seems like Twitter decided to sacrifice usability for branding purposes, yet advertising it as if they care about users. The part of the users’ disappointment should have been caused by this contradiction.

Yet there are plenty of other reasons for driving users mad. Chirp has visible issues with displaying on Windows, that Twitter promises to fix soon.

Another thing is a problem with multilingual support. For some reason, Chirp doesn’t have a Greek and Cyrillic character set, or those sets don’t work as they should. Lots of people say their non-English posts look noticeably different from the Latin text.

People would probably accept the problematic default font if only they could change to a preferable one. But such functionality is not available on Twitter.

Looks like I got a headache during the work on this article, and the text tends to be too critical of Twitter. To correct the balance, I would like you to meet Maksym, UI/UX designer at Eleken. He likes Twitter’s redesign, and here’s why:

Except for the evocative shortcomings, Twitter’s design team made a bunch of invisible improvements. They removed minor inconsistencies, cleared the interface from visual clutter and simply made design elements work better together.

For instance, they changed the color of navigation elements. Now you have black color for navigation and blue color for action buttons, and it makes much more sense than having everything in blue.

Users hate the new contrast mode.

“Guys went too far with the contrast” — Maksym says, on the contrary. He believes contrast change became the most problematic aspect of Twitter’s redesign, even though most people blame the new font.

Low contrast in design causes problems for people with low vision or color-blindness. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) require the contrast ratio for text to be at least 4.5:1, but it doesn’t regulate the upper limit.

Twitter’s example showed that the high contrast that exceeds the specified minimum can be also a bad idea, especially for users who suffer from chronic migraines.

A significant part of complaints about headaches and eyestrain was probably caused not by the font itself, but by the increased gap between the color of the font and the color of the background.

The good news is that Twitter acknowledged the contrast problem and promised to fix it.

The bad news is that Twitter didn’t promise to expand the contrast customization capabilities so that users could change the contrast to whatever works best for them.

Users hate new buttons (but probably shouldn't).

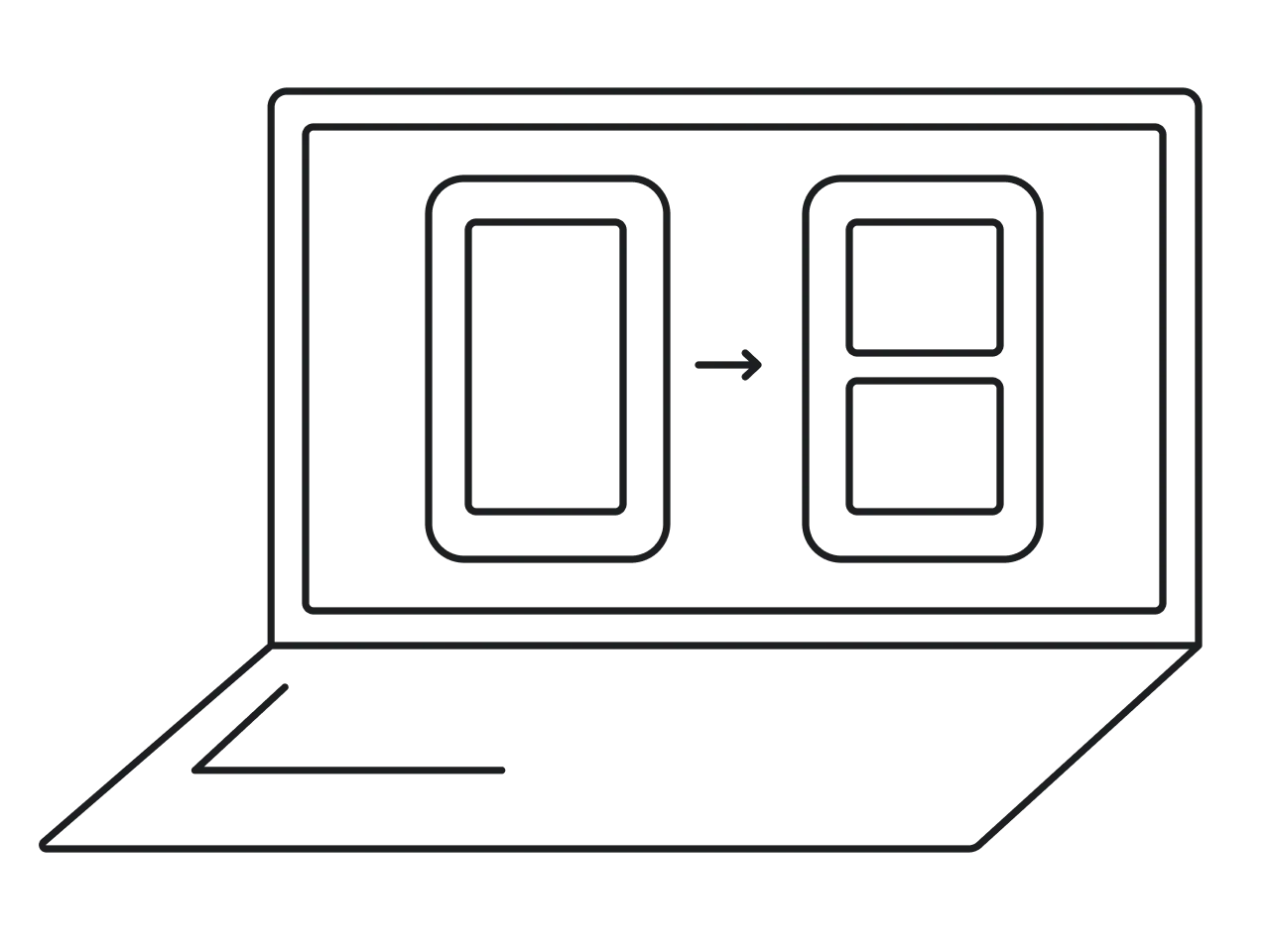

Another hotly debated change is the colors inversion of the "Follow" and "Unfollow" buttons. Users habitually hit unfilled buttons to follow people… And accidentally unfollow them. Pretty annoying, but there's an explanation for this upside-down move.

Dann Petty says the following button was broken before, and now it is fixed. The app shows two buttons simultaneously, for tweeting and for following people. Those buttons used to be blue and white — to make them different and avoid user confusion.

Now, what happened after you followed somebody?

The unfollowing button turned blue, just like the tweeting button, bringing you back to the problem with visual hierarchy.

The recent redesign has solved the problem by making the second-priority following button gray. As you follow someone, the button turns white and stops drawing your attention. It’s just like YouTube’s "Subscribe" button goes from red to grey when activated, and Instagram’s "Follow" button goes from blue to white.

So even if the new buttons will annoy us until we learn to live with them, they were redesigned for greater usability good.

What can we learn from Twitter’s mistakes?

Twitter’s redesign showed what may happen if your users wake up to see changes they didn’t ask you for. That’s an important lesson for any SaaS company — automatic updates are as much of a liability as a strength.

Another lesson is that there’s no one-size-fits-all accessibility. Integrate a wide range of disabled people for testing before your design goes live.

And finally, make changes an option, not a default. Let people customize the design to whatever works best for them.